Manzanar National Historic Site

Manzanar National Historic Site – Owens Valley, CA

3

SEPTEMBER 2015

I visited the Manzanar National Historic Site quite by accident. It was September 2015 and I was driving to the Las Vegas Airport after my Sierra Nevada hike. The alternate route I had decided upon down US-395 would take me through Death Valley. As I was driving through the stark but scenic Owens Valley, with Mt. Whitney looming to the west, I saw a sign for Manzanar National Historic Site. I knew about Manzanar, a World War II Japanese internment camp, but I had never had the desire to make a special visit. But I was there and I had plenty of time before my flight so I decided to stop and explore.

“As far as I’m concerned, I was born here, and according to the Constitution I studied in school, I had the Bill of Rights that should have backed me up. And until the very minute that I got on the evacuation train, I says, ‘It can’t be.’ I says, ‘How can they do that to an American citizen?'” – Robert Kashiwagi

A brief history of the Manzanar Historic Site

Manzanar is the site of one of ten American concentration camps where more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. In March 1942 Manzanar was the first to be established. By mid–April 1942, up to 1,000 Japanese Americans were arriving daily, and by July 1942, the population of Manzanar reached 10,000. Manzanar was closed when the final internee left on November 21, 1945. Up to 146 Japanese Americans died at Manzanar. Within a couple of years of closure, all the structures had been removed except three – two sentry posts and the auditorium. In February 1985, Manzanar was designated a National Historic Landmark. On March 3, 1992, Manzanar was designated a National Historic Site. The National Park Service was given control and led efforts to restore the site.

The Manzanar National Historic Site Interpretive Center

The Interpretive Center is located in the auditorium building, one of three original structures still located on the site. The Interpretive Center houses exhibits of historic photos, film footage, audio programs, a scale model of the camp, and a children’s exhibit. There is also a 22-minute film about the camp as well as a bookstore and Junior Ranger program. The auditorium, where the Visitor’s Center is located, was the center of life at Manzanar. There was a stage, locker rooms, and a film projection booth. Concerts, lectures, movies, dances, and other activities filled the auditorium’s calendar as well as its 1,280-seat capacity. Tickets for events were 5 cents for children, 25 cents for adults, and 50 cents for camp staff.

Block 14

The National Park Service has restored parts of Block 14 to give visitors an idea of what block life was like in the camp. There were 36 similar blocks when Manzanar was active. Two barrack buildings were reconstructed in 2010. Building 1 represents the camp in 1942, and building 8 shows camp life in 1945. The block 14 reconstruction also features a section of the camp perimeter fencing, a basketball court in the adjacent South Firebreak, and a restored World War II-era mess hall. There are plans for future restorations of the latrines, laundry room, and ironing room. I was the only visitor at the time I was there, and in the stillness, it wasn’t hard to imagine the heat in the summer, cold in the winter, and dust that must have dominated camp life.

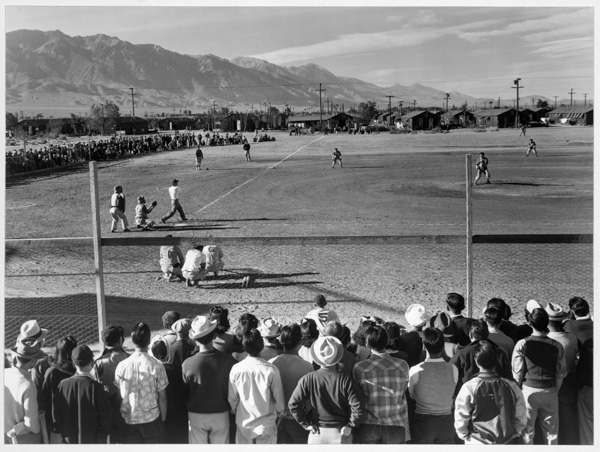

Baseball Fields

It’s hard to imagine it now but thousands of fans would gather for baseball games on Manzanar’s main baseball field located in the North Firebreak. By the summer of 1942 Manzanar had 12 different baseball leagues with 100 men’s teams and 14 women’s teams. Baseball boosted morale and helped combat the ever-present boredom of camp life. Baseball was a huge part of American life and playing it gave internees some sense of normalcy. One internee, Takeo Suo, was quoted as saying “Putting on a baseball uniform was like wearing the American flag.” During my visit, I wandered around the long-abandoned fields and imagined what it must have been like. The home plate and pitcher’s rubber were still there.

Japanese Gardens

There were over 100 gardens on the Manzanar site. They served as important family gathering spaces and children’s play areas. After Manzanar closed, the gardens were bull-dozed or filled with debris when the camp was dismantled. Starting in 1993, the National Park Service began efforts to uncover and stabilize the gardens. Twenty of the gardens have now been excavated and stabilized.

Manzanar Cemetery Monument

On May 16, 1942, Matsunosuke Murakami, 62, became the first of 150 men, women, and children to die in Manzanar. He was buried in a cemetery at the back of the camp. In 1943 Ryozo Kado designed the cemetery monument as a tribute to Manzanar’s dead. The monument was funded by 15-cent donations from each family in camp. The Japanese Kanji characters on the monument read “Soul Consoling Tower.” By 2014 monument was in disrepair and in need of restoration. The National Park Service took on the restoration, which was completed in October 2014. I’m happy they did. At the time of my visit in 2015, the cemetery monument was in pristine condition. The pristine monument against the mountain background was an awesome sight.

Conclusion – Manzanar National Historic Site

I know the times were very different in 1942 when Manzanar was established. The US government was nearly panicking over potential Japanese war plans on the west coast. But it still seems unfathomable that our country would forcibly remove US citizens and place them in what amounted to a prison or concentration camp. The restored guard tower on the camp’s perimeter clarified what Manzanar was – a prison. Conditions in Manzanar must have been horrible. The barracks were not designed to deal with the 100-degree temperatures in summer and sub-freezing temperatures in winter. The wind blew constantly, and dust was ever-present. Though it is a somber and somewhat depressing place to visit, I am glad I did. It was an important lesson about a difficult time in our country’s history. If you’re ever in the area, it’s worth the time to stop and explore Manzanar National Historic Site.